Within the last ten days, the Academy has made two inspired laureate selections that, when revealed, had the appearance of nothing less than magic (def. the art of elegant misdirection). The likely winner of the Nobel Peace Prize kept the people at Ladbrokes and the Las Vegas Sports Book crazy for days. A multitude of names were tossed around, including some of the academy's customarily compelling choices from the developing world -- as well as a few zingers, for the sake of sexing up an awards ritual quite long in the tooth.

For their own personal endeavors for addressing some of the world's enduring problems -- debt relief, famine relief, affordable AIDS therapies -- Live Aid architect Bob Geldof and Bono of U No Who 2 were nominated. Theirs were long-shot chances; Bono graciously admitted as much the night before the announcement, telling Conan O'Brien it was just an honor to have been nominated.

The winner of the Nobel, a man who was said to be on the short list but somehow got lost in the wash of current events, hit like a clap of thunder: The director of the International Atomic Energy Agency, Mohammed ElBaradei, shared the $1.3 million prize with the agency that tried to act as an honest, reasonably non-ideological broker between the Middle East and a fractious Washington. ElBaradei's award was widely perceived as a global/philanthropic two-by-four to the head of the administration, which had done battle with ElBaradei in the past, as recently as the summer, when the United States opposed ElBaradei's reappointment as IAEA director. The choice was, well, inspired. And there was more.

The winner of the Nobel, a man who was said to be on the short list but somehow got lost in the wash of current events, hit like a clap of thunder: The director of the International Atomic Energy Agency, Mohammed ElBaradei, shared the $1.3 million prize with the agency that tried to act as an honest, reasonably non-ideological broker between the Middle East and a fractious Washington. ElBaradei's award was widely perceived as a global/philanthropic two-by-four to the head of the administration, which had done battle with ElBaradei in the past, as recently as the summer, when the United States opposed ElBaradei's reappointment as IAEA director. The choice was, well, inspired. And there was more.Harold Pinter, long acknowledged as the lion of British theater for the second half of the twentieth century, and lately an avowed opponent of the U.S.-led initiative in Iraq, won the Nobel Prize for Literature. The Academy hailed Pinter as a playwright "who in his plays uncovers the precipice under everyday prattle and forces entry into oppression's closed rooms."

A kind of prolonged howling was observed coming from the West Wing that evening, followed in short order by the customary conservative outrage. It was the second pointed rebuff-by-proxy of the American misadventure in the Middle East.

And what might be seen in isolation as the rogue reflex of intellectuals in one of the world's enduring pacifist nations is actually something wider. When culture is pushed, sooner or later, culture pushes back. It's happening now, building on previous successes, and taking advantage of a slow groundswell of opposition to the war in Iraq. And not just at the investiture-and-morning-coat level of the Nobel Prize. It's happening, again, at the multiplex near you.

With "Good Night, and Good Luck," George Clooney's masterful glimpse at one high point in the clash between Edward R. Murrow and Sen. Joe McCarthy, the reigning device of popular culture managed to tell a contemporary American story through the images of an older one, the demagoguery of an earlier uncertain age suddenly a mirror on the slicker, more camera-ready demagogues of the present day. "We will not walk in fear," Murrow says. "We cannot defend freedom abroad by deserting it at home." The linkage of then and now couldn't be more real, more pointed, more indicative of a tide beginning to turn.

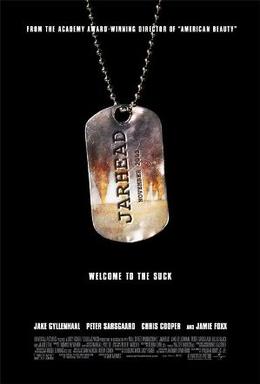

Then there's "Jarhead," Sam Mendes' treatment of Anthony Swofford's chronicle of a Marine's wrenching, emotionally expensive transition from raw boot-camp recruit to sniper in the first Gulf War. And on Dec. 9, we'll have "Syriana," Clooney's next film, a political thriller that plumbs the interplay of rapacious U.S. oil companies and the disillusioned of the Middle East, who find solace and meaning in pursuing violent work against the West. The film, written and directed by Stephen Gaghan ("Traffic"), seems likely to be a project to exercise Clooney's maverick streak for candor, and opposition to policies and practices the administration holds dear.

Then there's "Jarhead," Sam Mendes' treatment of Anthony Swofford's chronicle of a Marine's wrenching, emotionally expensive transition from raw boot-camp recruit to sniper in the first Gulf War. And on Dec. 9, we'll have "Syriana," Clooney's next film, a political thriller that plumbs the interplay of rapacious U.S. oil companies and the disillusioned of the Middle East, who find solace and meaning in pursuing violent work against the West. The film, written and directed by Stephen Gaghan ("Traffic"), seems likely to be a project to exercise Clooney's maverick streak for candor, and opposition to policies and practices the administration holds dear. So what's different? "Fahrenheit 9/11," released in early 2004, couldn't have the benefit of hindsight. For all its impressive splash into the culture (it was the first documentary to gross more than $100 million at the box office), Michael Moore's masterpiece could only take us so far into events that were occurring as the film went into post-production. Now, there's a sense, broadly supported by numerous opinion polls, that the populist underpinning of antiwar sentiment is way broader than before, in the angrily heady months after Sept. 11.

What's different? More and more Americans are against the war in Iraq, and unlike before, they're increasingly willing to say so. And since culture, high and low, is the basis for so much of our everyday identification -- the fabric of the national conversation -- that antiwar sentiment takes on a life and a resonance it didn't have before.

Our culture, like our society, is always subject to change; the slow perforation of a tissue of lies is underway, and you get to watch it with popcorn in your lap.

When culture's pushed, sooner or later, culture pushes back.

-----

Image credits: ElBaradei: IAEA. Jarhead poster: Universal Studios.

1 comment:

An inspiring 'taste of sin'

She may have mastered the art of French cooking, but don't call amateur cook-turned-author Julie Powell a foodie.

Great blog, very interesting. I bookmarkedalready. I have a income opportunity site. it has income opportunity INFORMATION, It is great is you want to quit your job:-)

Post a Comment