But as the smoke clears around the Kodak Theater, the question persists: Why did "Brokeback Mountain" -- all but coronated Best Picture beforehand -- fail and the more diffidently received "Crash" succeed? Los Angeles Times film critic Kenneth Turan observed that despite "Brokeback's" success, “you could not take the pulse of the industry without realizing that this film made people distinctly uncomfortable.”

But as the smoke clears around the Kodak Theater, the question persists: Why did "Brokeback Mountain" -- all but coronated Best Picture beforehand -- fail and the more diffidently received "Crash" succeed? Los Angeles Times film critic Kenneth Turan observed that despite "Brokeback's" success, “you could not take the pulse of the industry without realizing that this film made people distinctly uncomfortable.”“In the privacy of the voting booth," Turan wrote, "people are free to act out the unspoken fears and unconscious prejudices that they would never breathe to another soul, or likely, acknowledge to themselves. And at least this year, that acting out doomed ‘Brokeback Mountain.”’

Still, despite "Brokeback's" fate, and whether Sunday's Oscar outcome was a reaction to the undercurrent of conservatism in post-9/11 America, or a more organic shift in understanding how the nation thinks and feels today, the Oscar Experience 2006 was more open-minded, emotionally and stylistically democratic, unabashedly liberal and multicultural than it's been in some years.

"Brokeback Mountain," the story of two cowboys and their romantic experience over twenty years, was odds-on favorite to win for Best Picture. Had been all this year and part of last year, too. But all the talk about "Brokeback" obscured other nominated films exploring other lives in the American dynamic.

"Capote" stars Philip Seymour Hoffman in a true star turn as Truman Capote, in a story about the writer's journalistic coverage of the Clutter family murders and the two men responsible for them. Hoffman, for some time now considered an actor's actor, is spot on as Capote; the fact that Hoffman was nominated for his portrayal of a gay cultural icon, as well as a celebrated figure of American letters, is a refreshing departure for the Academy.

"Capote" stars Philip Seymour Hoffman in a true star turn as Truman Capote, in a story about the writer's journalistic coverage of the Clutter family murders and the two men responsible for them. Hoffman, for some time now considered an actor's actor, is spot on as Capote; the fact that Hoffman was nominated for his portrayal of a gay cultural icon, as well as a celebrated figure of American letters, is a refreshing departure for the Academy. Another one was the nomination of Felicity Huffman as Best Supporting Actress, for her role in "Transamerica," the story of a man preparing for sex-change surgery.

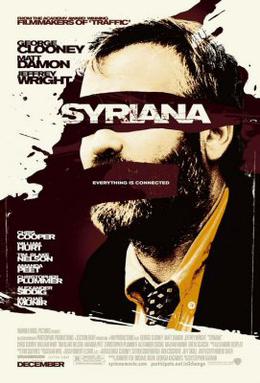

And the Academy clearly had a wet spot for agent provocateur George Clooney, double-nominated for Best Director for "Good Night, and Good Luck," his story of the clash between CBS newsman Edward R. Murrow and Sen. Joseph McCarthy, and for Best Supporting Actor for "Syriana," a story of intrigue and government deception set in today's Middle East.

You had a sense of where things were going when Ang Lee won as Best Director for "Brokeback." That discomfort some Academy members had about the film didn't extend to the director, who we understand is genuinely loved in Hollywood. But clearly the wheels were turning: How to honor the director and benignly register the discomfort about the film he directed? And how best to give due props to "Crash," a film whose look at contemporary Los Angeles resonates both as reality and urban myth to the Academy voters, who live there?

The Academy split the difference, making Ang Lee the first nonwhite guy to win as Best Director, and elevating "Crash" to Best Picture in an upset win that cemented its little-engine-that-could status, a victory that partially redeemed the train-schedule regularity of the broadcast.

Again, the Academy's willingness this year to accommodate stories on a man switching genders, a flamboyant gay writer, two secretly gay cowboys, a liberal take on Republican Joe McCarthy and a less than flattering look at U.S. intelligence in the Middle East may be nothing more than the Academy response to great performances of great roles by great actresses and actors. But nothing in America happens without a context. Nature may abhor a vacuum, but popular culture loves an echo chamber.

It's hard to buy the idea that these films arriving on the American scene at this time is just coincidence. It takes too long to make and market a movie to rely on happenstance; for better or worse, the making of a motion picture may be our abiding pop-cultural example of what psychologist Irving Janis, in 1972, called groupthink: a situation "when the members' strivings for unanimity override their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action."

It's hard to buy the idea that these films arriving on the American scene at this time is just coincidence. It takes too long to make and market a movie to rely on happenstance; for better or worse, the making of a motion picture may be our abiding pop-cultural example of what psychologist Irving Janis, in 1972, called groupthink: a situation "when the members' strivings for unanimity override their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action." But the arrival now of these films, whose subjects and stories run counter to the conservative groupthink of today's America, suggests that some creative forces in American life think the wheel is starting to turn -- that the lives of gays, lesbians and transgendereds deserve equal cinematic opportunity; that the duplicities of American spycraft generate a host of unintended victims this nation would rather not know about; that a story of journalists battling the U.S. government of fifty years ago is as pertinent today as it was back then, and maybe more so.

As always, Clooney got it just about right -- pitch-perfect, really -- after winning the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for "Syriana." Accepting the award, he relished the role of the artist (Academy member, actually) as an outsider in American society. Clooney deftly turned the conservative indictment of the entertainment industry -- that they're "out of touch" with mainstream America -- back on itself, in a masterful embrace of outsider status Hillary Clinton would do well to evaluate.

In a nutshell Clooney gave artists, writers and all free thinkers reason to hold their heads high.

In a nutshell Clooney gave artists, writers and all free thinkers reason to hold their heads high. "I would say that, you know, we are a little bit out of touch in Hollywood every once in a while, I think. It’s probably a good thing. Uhm, we’re the ones who talk about AIDS when it was just being whispered. And we talked about civil rights when it wasn’t really popular. And we, uh, you know, we bring up subjects…we are the ones…this Academy, this group of people gave Hattie McDaniel an Oscar in 1939 when blacks were still sitting in the backs of theaters. I’m proud to be a part of this Academy. I’m proud to be part of this community. I’m proud to be out of touch."

Maybe it was the heat of the moment, but he didn't get it exactly right. On the March 6 edition of MSNBC's "Countdown" with Keith Olbermann, Village Voice writer and pop-cultural bete noire Michael Musto pointed out that black people were seated in the back of the hall when Hattie McDaniel won her Oscar -- the winner herself was escorted to a table in the rear of the Coconut Grove of the Ambassador Hotel -- and that Hollywood, far from being out in front on AIDS, came years late to the matter of addressing that dread disease (look how long after the epidemic hit before Tom Hanks won the Oscar for his work in "Philadelphia").

But in some other important ways, Clooney was right: It's the job of artists, he seemed to say, to act as the sentinels, the mavericks, the canaries in the coal mines of society, the little kid in the crowd who's not afraid to call the emperor on his wardrobe. And never mind the concerns about industry grosses and box-office receipts, and the other typical retorts of those who can't see what really stands for progress:

But in some other important ways, Clooney was right: It's the job of artists, he seemed to say, to act as the sentinels, the mavericks, the canaries in the coal mines of society, the little kid in the crowd who's not afraid to call the emperor on his wardrobe. And never mind the concerns about industry grosses and box-office receipts, and the other typical retorts of those who can't see what really stands for progress:From all the nominated films to other films like "Lords of War" and "God Sleeps in Rwanda" that didn't get the Academy's attention this time, to other films still in the brains and keyboards of writers we haven't heard from yet, there's abundant evidence that the old laws of who wins, who loses and who participates in Oscar Hollywood have changed permanently.

Sometimes -- usually, even -- the Big Picture emerges from the smaller ones.

-----

Image credits: Ang Lee: Taiwan Government (public domain); Syriana: Warner Bros. Brokeback Mountain: Universal Pictures

No comments:

Post a Comment